Risk assessment is used to hugely-beneficial effect in many industries, ranging from off-shore oil and gas to nuclear and transportation. It is also used to plan for health epidemics, food safety and flooding. Generally the methods deployed are highly sophisticated, science-based and provide useful information for decision makers.

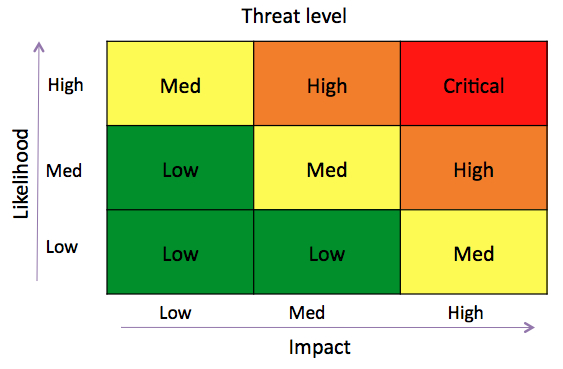

In recent years risk assessment has also been applied to public space and public activities, often using, by necessity, much simpler protocols such as HSE’s ‘Five steps to risk assessment’ (http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg163.pdf), or devices known as risk matrices of the type shown below which may range from 2×2 to even 10×10 cells.

These matrices, and the way they are used, are a source of worry for some eminent risk practitioners. For one thing they are usually qualitative in that there are no numerical values on either axis and both risk and consequence are subjectively-defined. What, for instance, does it mean to say something has a ‘medium’ likelihood? And in the case of public space is it the likelihood of something happening to one individual member of the public on a single visit, or on multiple visits over a year, or is it the likelihood that any member of the public might come to grief during, say, the next month? There are numerous possibilities but most matrices seem to leave this question unanswered despite having massive implications for their meaning.

Another technical anxiety is that users quite often number the cells along each axis from, say, one to three in the case of the matrix shown, and then multiply them together to generate a score for each cell. In this way the top right cell in the matrix shown would score 9, and the bottom left 1. This is troubling for several reasons. For one thing the axes are qualitative and labelling them from 1 to 3 produces ordinal numbers only (as in first, second, third etc), and not cardinal numbers. It never has made sense to multiply ordinal numbers together.

Another matter is that when numbers are multiplied, however ill-advisedly, they are sometimes said to be used as a means of prioritising and the aim of many risk assessors appears to be to shift hazards falling in the red-coloured boxes to the green ones. The requirement under the law, however, and which is deeply rational, is that control measures should be implemented if they are reasonably practicable. This is a much more sophisticated concept and is not replaceable by fiddling with coloured squares on grids. It could mean that hazards in higher-scoring boxes should not be subject to further control measures because there are none which are reasonably practicable.

An altogether different issue comes up when considering the risk assessment of public space and public activities, and this relates to the reason for their provision which is, obviously, their benefits. Public facilities, such as city squares, tree-lined streets, ponds and fountains, riverside walks, parks, playgrounds, forests, church yards, sites of cultural heritage, national parks, village fêtes, carnivals and sports of whatever kind produce benefits of all kinds ranging from health (physical, emotional and social) to intellectual stimulation, beauty and tranquillity. The problem is that these benefits get no mention in standard risk assessment protocols. It is as if the decision about whether, say, a public activity should be permitted or curtailed could be made purely by thinking about its inherent dangers and without any need to consider the benefits of the activity. This would be an irrational decision process. There is almost always some sort of trade-off between control measures and benefits when dealing with public places and public activities and it is essential that this be recognised, not ignored.

In effect, what has to be done is to weigh the benefits of, say, an unspoilt riverside walk and its risks, and make a decision on whether it should be left as it is or modified. This approach, of weighing risks and benefits, is what is increasingly being referred to as risk-benefit assessment (RBA). If you try to make this decision without thinking about either one of these commodities, the risks or the benefits, I for one could not conceive what was going on in the risk assessor’s head. But I suspect these for me unfathomable thought processes are quite common given that standard risk assessment protocols only refer to one side of this equation, leaving it open to ignore or forget the other.

Collectively these issues suggest that risk assessment as used in public life may require radical surgery.