This year’s London marathon saw the tragic death of Claire Squires. Subsequent media stories revealed that Claire’s was the eleventh such death since the event began in 1981. From this one can (in a sense) gauge the relative riskiness of marathon and long distance running as a sport. From 1981 until 2012 there have been about 850,000 competitors. Taking 4 hours as a rough race time means that competitors have collectively spent around 3.4 million hours on the course. A sometimes used risk statistic for comparative purposes is the death rate per 100 million hours of an activity, known as the FAR (Fatal Accident Rate). From this:

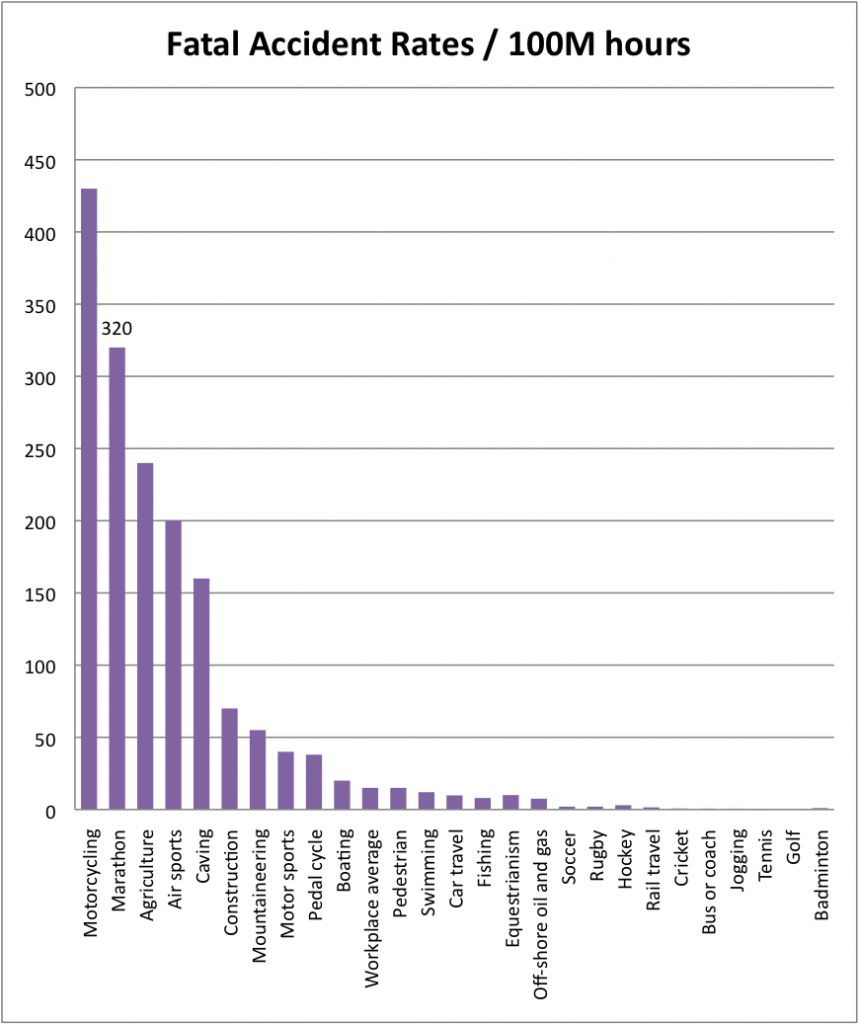

FAR for London marathon ≈ (100/3.4) x 11 ≈ 320 fatalities per 100 million hours

How does this compare with other sports and other activities? Back in 1998 I made a study of fatal and non-fatal accident rates for a range of sports ranging from mountaineering to badminton (J. Sports, Exercise and Injury, 1998; 4:3-9). At that time the data showed the most dangerous sport was that categorised as ‘air sports’ which included aerobatics, gliding, hang-gliding, micro-lights, paragliding etc, and which had a FAR in the region of 200. Mountaineering was next highest coming in the range of 30-60, but has since been displaced into third place by caving which comes in at about 160. Water-related sports such as swimming, boating and fishing all have FARs of around 10 to 20, and horse riding comes in at 10. Sports such as rugby, soccer, hockey, cricket and badminton lie in or close to the range of 1 to 3.

From this (see histogram) it can be seen that marathon running is at the high risk end of the spectrum in terms of the FAR yardstick when compared with other sports. This is also true if compared even with industries operating in challenging environments, such as offshore oil and gas, where the FAR as reported by the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers is in the range of 5 to 10.

More generally, within the UK, occupational fatality rates can be estimated from HSE statistics. The average FAR for all workers is around 15, rising to around 70 in construction and 240 in agriculture. Likewise, Department for Transport statistics report FARs for various modes of travel: car 9.8; motorcycle 430; pedal cycle 38; pedestrian 15; bus or coach 0.63; rail 1.5.

So if marathon running is so risky why do it? The answer is that participation brings huge rewards in terms of physical fitness and health, psychological benefits, and social ones too. Even businesses benefit. But the debate over the relative merits and demerits of participation in these kinds of relatively extreme pursuits has been with us for thousands of years. When the London marathon was first proposed by Chris Brasher and John Disley in the 1970s there were objections, for example, that entrance should at least be restricted to club athletes. And during the earlier 1967 Boston marathon a race official attempted to physically eject Kathrine Switzer from the supposedly all-male event on the grounds that “Anything long like 800m, or even longer, God forbid, was considered dangerous ………” for women.

Times, and views, have clearly changed, and to some extent this has been unavoidable given the accumulating evidence of the health benefits of sport. Thus, in the nineteenth century, the view of Reverend Charles Wadsworth, with reference to the Oxford and Cambridge boat race, that ‘no man in a racing boat could expect to live to the age of thirty,’ was gradually proven wrong by epidemiological research which showed life expectation to be greater for rowers than non-rowers by several years.

For a concise and enthralling account of the history of beliefs surrounding the benefits or otherwise of physical activity, see Domhnall MacAuley’s ‘A history of physical activity, health and medicine’.

The debate, of course, continues. But it does illustrate the importance of collecting evidence and not being overly reliant upon subjective opinion and prior beliefs.